THE RISE OF THE NETWORK CAMPUS

MSc 3 Hybrid Buildings, Architectural Research

By Richard Hagg

INTRODUCTION

In this paper I will investigate the impact of the technological, and social changes, as a result of the ‘Rise of the Network Society’[1], on campus design.

From the 1970s onwards the information technology revolution initiated a major change in our postwar, industrial society. As Manuel Castells puts it: ‘... a sudden, unexpected surge of technological applications transformed the processes of production and distribution, created a flurry of new products, and shifted decisively the location of wealth and power in a planet that became suddenly under the reach of those countries and elites able to master the new technological system.’[2]

This surge, this revolution, not only transformed processes of production and distribution, and initiated power shifts, but transformed society as well. The industrial society is transformed towards a network society. Through the introduction of personal computers, the internet and the growth of mass media, the way in with people organize and live their lives at home, in public, at work and at schools is changing. It is the latter that will be the focus of this paper.

It will not come as a shock when I tell you that a great deal of the information technology revolution originated from within the academic realm. One of the first networks was that of academic knowledge exchange, and much of the technological development was founded within universities. ‘This university origin of the Net has been, and is, decisive for the development and diffusion of electronic communication throughout the world.’[3] Since the university is one of the ‘…furnaces of innovation in the information age…’[4] I hypothesize that the physical place of the university is changing under the influence of the rise of the network society. I will argue, by example, that the major characteristics of the network society are the foundations for the change in campus design.

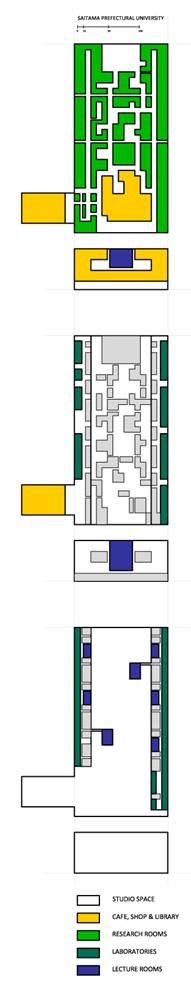

SAITAMA PREFECTURAL UNIVERSITY

In 1999, approximately 30

years after the initiation of the information technology revolution, the

Saitama Prefectural University is built in the city of Koshigaya, Japan. This

university, designed by Riken Yamamoto, is dedicated to health care. It is

composed of a newly established four-year college and a junior college, with

curriculums in nursing, social welfare and rehabilitation. The almost 35,000 sq

meter structure houses the departments of Nursing, Physical Therapy,

Occupational Therapy, Social Work and Health Sciences.

In 1999, approximately 30

years after the initiation of the information technology revolution, the

Saitama Prefectural University is built in the city of Koshigaya, Japan. This

university, designed by Riken Yamamoto, is dedicated to health care. It is

composed of a newly established four-year college and a junior college, with

curriculums in nursing, social welfare and rehabilitation. The almost 35,000 sq

meter structure houses the departments of Nursing, Physical Therapy,

Occupational Therapy, Social Work and Health Sciences.

Photos by Ohashi Tomio

The Saitama Prefectural University is designed as two 400

meters long, parallel structures connected through a one-storey ‘landscape’. Each

of these parallel structures houses one of the two colleges and their

laboratories, but the entire first floor consists of study rooms for both. Both

structures have a linear organization with a media gallery as its centre line. This

media gallery connects the laboratories and study rooms and thereby promotes an

interrelationship between students of both colleges and between students and

faculty members.

UNIVERSITY OF HAKODATE

Photo by Matsuoka Mitsuo

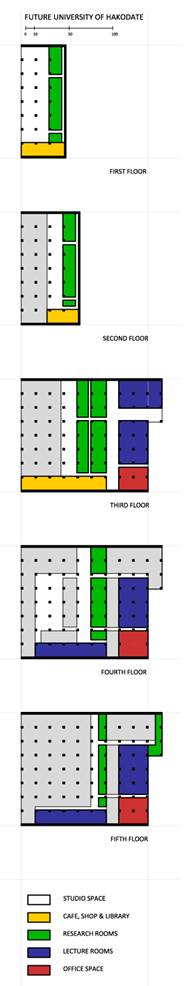

In 2000, one year after the completion of the Saitama

Prefectural University, the Future University of Hakodate, Japan is built. This

13,000 sq meter university of information science, also designed by Riken

Yamamoto, houses the departments of Complex Systems and Information Architecture.

Photo by Fujisuka Mitsumasa

The two departments are

designed together in one ‘large, all-encompassing space’[5]. Within

this space the research rooms are organized in a stepped configuration on the

sloping site. Through this organization, studios are created adjacent to a

large void in which students can create their own space. These studio spaces

form the centre of activity and this is where students and faculty members can

interact.

The two departments are

designed together in one ‘large, all-encompassing space’[5]. Within

this space the research rooms are organized in a stepped configuration on the

sloping site. Through this organization, studios are created adjacent to a

large void in which students can create their own space. These studio spaces

form the centre of activity and this is where students and faculty members can

interact.

Before investigating these two universities in more detail, we will

explore a number of characteristics of the Network Society related to the topic

of campus design.

CONNECTIVITY AND COMMUNITY

Although the Saitama

Prefectural University and the Future University of Hakodate show great

programmatic resemblance with universities from before the information

technology revolution, the underlying ideologies and the way they are organized

can be explained as the result of a knowledge-information based, network

society.

Although the Saitama

Prefectural University and the Future University of Hakodate show great

programmatic resemblance with universities from before the information

technology revolution, the underlying ideologies and the way they are organized

can be explained as the result of a knowledge-information based, network

society.

‘The emergence of new electronic communication system characterized by its global reach, its integration of all communication media, and its potential interactivity is changing and will change forever our society.’[6] Only twenty years after the introduction of these new electronic communication systems – that of the U.S Defense Department and the academic society – in 1969 and the first micro computers in 1975, the world started to be ‘wired’ together by the Internet and other global media. At a staggering pace economics, politics, education, companies and other institutions became part of ‘global networks of wealth, power and symbols’[7]. This development of networks and globalization surprisingly not only created a sense of equality and/or sameness, because of the de-territorializing and de-materializing effects of those networks, but also created a stronger sense of identity; for with whom or what do we identify ourselves, when borders and physical differences are fading. As Manuel Castells puts it: ‘Our societies are increasingly structured around a bipolar opposition between the Net and the Self.’[8]

More recently, within the duality of the Net and the Self, we can identify a common denominator. We do not focus solely on the gap between the collective and the individual anymore, but on their common ground. ‘Collectivity has made way for connectivity, and the indivisible, sovereign, choosing individual for a subjectivity, distributed over many networks.’[9] These networks connect us, not with the collective Net, but with multiple ‘modern’ communities; small communities of individuals who share the same interests and/or ideas, spread all over the world. Through the developments of small communities, the Net loses much of its collective character.

It is this connectivity of small communities that is recognized in the two universities at hand.

UNIVERSITY AND IDEOLOGY

Riken Yamamoto proposed that the Saitama Prefectural University, dedicated to nursing and social welfare, was to establish a close relationship with society. He suggested that all the different departments should be interrelated and thereby create a network of knowledge and expertise. This micro-network will in its turn connects to a greater, social network. It will diffuse its knowledge into society through an in-house health centre, a library and of course the Internet.

The Future University of Hakodate presents us with a similar connectivity, but within an even smaller community; it emphasizes on the connectivity between student and faculty. It is designed in the assumption that an open (space) network of students and faculty members contributes to a greater collective of knowledge and ability (‘open space = open mind’[10]). We cannot say that this theory is one of recent times, but it is very recognizable within the subject of the Network Society.

The university already lost the image of being a closed-off and self-sufficient place for theoretical and individual/personal development, but now it is becoming more a connected node of information and knowledge within a small, social network.

‘Indeed, against the assumption of social isolation suggested by the image of the ivory tower, universities are major agents of diffusion of social innovation because generation after generation of young people go through them, becoming aware of and accustomed to new ways of thinking, managing, acting, and communication.’[11]

Through the development of the networks, the exchange of knowledge and information within the university and towards their ‘communities’ becomes even more essential.

RESEARCH AND EDUCATION

The development in education, from the ivory tower to a node of knowledge within a network, reflects on the means of research and education. Because universities and other research and education institutions act as nodes of knowledge within society, they take on a more practical and efficient way of knowledge and information generation and exchange.

‘ ..the development of the information technology revolution contributed to the formation of the milieu of innovation where discoveries and applications would interact, and be tested, in a recurrent process of trial and error, of learning by doing; these milieus required (…)spatial concentration of research centers, higher education institutions…..’ [12]

Universities started to adjust to the process of learning by doing, because this practical approach to knowledge and information exchange reinforces their position as a knowledge node within a certain society. Simultaneously, university departments started to increase their range of knowledge by learning from other disciplines, in order to fully comprehend their position within a process or community. Because of these shifts, new systems of organization and communication within universities became desirable.

ORGANIZATION AND LOCATION

Do the aforementioned new systems of organization and communication changed campus design? Gunter Henn argues that architecture needs to transform the physical place to these shifts in education, but simultaneously acknowledges the fact that the university itself is connected to society more strongly through virtual networks than its actual physical location.

‘Through the potential of the media and mobility, our world is mainly structured by networks that functions independently of real physical places. Nodes form in these networks, which at certain points take on firmness of places where time is spent. Architecture must react to these new localities and communication nodes with specific design and spatial elements, even though under different auspices and with introduction of new technologies. ‘[13]

This duality between the ‘virtual’ and the ‘physical’ raises the question if the physical place of the university indeed needs to change in a world that functions independent from the physical place. To be connected to virtual networks, introducing computers (connected to the internet) would be the only change needed in the physical place.

We have to understand that it is not the position of universities as nodes of knowledge within society, but the changes within universities themselves to be able to function as an interdisciplinary and connected network within this larger network of society, that is changing the physical place of universities.

When we look at the two

universities at hand and compare them with the developments in ideology, education

and organization, we will see great resemblances.

When we look at the two

universities at hand and compare them with the developments in ideology, education

and organization, we will see great resemblances.

THE NETWORK CAMPUS

The Saitama Prefectural University and the Future University of Hakodate can be explained as network campuses; they both are organized as networks. When investigating their plans, we can recognize that organization. They both use space as ‘…the material support of time-sharing social practices’[14] and organizes themselves around the interacting between students and between students and faculty members.

In the adjacent schemes of the Saitama Prefectural University it is made clear how the research rooms are organized within a network of open studio space and with the media gallery. Within these open spaces it is where the network is ‘physical’. This is where students from both colleges and faculty members have the opportunity to exchange knowledge and experiences; this is where they can ‘network’. The Future University of Hakodate, although the plans appear very different, is organized in the same way. Adjacent to the research rooms, the students and faculty members use the same type of open studio space for exchange of knowledge and experiences.

The studio spaces and media galleries support the system of education as well; the physical space is customized to a 'learning by doing' philosophy. The plans show the emphasis on the studio spaces and the subordination of auditoria and lecture rooms. This contributes to the importance of the ‘doing’ in education and the active exchange of knowledge between students.

Simultaneously, they are organized to contribute to interdisciplinary research and education; ‘The design of knowledge spaces is based on the changing of space- and time-dependent frameworks’[15]; students from both colleges have the ability to use studio space when they need to share time and space in order to work together. Although in the Saitama Prefectural University there still is a clear physical distinction between the two colleges, both universities acknowledge the fact that they have to be able to look beyond their own domain. By connecting different fields of expertise, and thereby taking on an interdisciplinary character, they enlarge their framework and strengthen their relevance to their community and to society; they can act as nodes in a larger network.

The Saitama Prefectural

University positions itself within the community of health care by connecting

their faculty and its students to a community outside the university; that of

the ill, disabled and less fortunate amongst society. The university is

connected to this small community, as mentioned earlier, through an in-house

health centre, a library and the internet; the university is made able to

re-direct their knowledge and expertise into their community.

The Saitama Prefectural

University positions itself within the community of health care by connecting

their faculty and its students to a community outside the university; that of

the ill, disabled and less fortunate amongst society. The university is

connected to this small community, as mentioned earlier, through an in-house

health centre, a library and the internet; the university is made able to

re-direct their knowledge and expertise into their community.

The Future University of Hakodate works within and connects to a larger and more obvious network, that of media and communication systems. This university specializes in fields that were part of the 1970s information technology revolution. But in fact, The Future University of Hakodate was designed as a much smaller community; an interdisciplinary university where multiple disciplines meet and interact.

Both universities show great resemblances with the developments in ideology, education and organization due to the rise of the network society. They are designed as nodes of knowledge, by using the open space studio as an ‘active’ place for knowledge exchange between students from different disciplines and connect them to their community.

CONCLUSION

in the 1970s the information technology revolution started to structure our societies ‘around a bipolar opposition between the Net and the Self.’[16] Now, 30 years later, we acknowledge that this duality actually connects us as individuals with smaller communities with the same interests and/or ideas.

Universities have become active, interdisciplinary nodes of knowledge within a certain community. The Saitama Prefectural University and the Future University of Hakodate stood example for the physical impact of these developments, in campus design.

Although early projects in architecture, such as the Free University of Berlin by Candilis, Josic and Woods, prefigure later ideas about networks and interdisciplinary information exchange, these Japanese examples explicitly address the question of knowledge development and exchange since the advent of the information society.

By focusing solely on the development of the Network Society and the two Japanese Universities, I was able to recognize similar developments in society and the academic realm.

Education and its physical place has changed under the influence of the rise of the Network Society. Campus design emphasizes on their relevance and connection to society or community. Therefore they take on a physical organization which stimulates a ‘learning by doing’ philosophy and encourages interaction amongst student, amongst different research fields, and between students and faculty members; The Network Campus is rising.